“In the hospital you’re on duty for 8 hours and if you get into trouble they’ll come and help you out. If you’re out in the district, you know, you sit there for 24 hours if they’re in labor and you really learn about labor. You learn all the physiology of childbirth and you have to know that and know it well before you can really apply your obstetrical knowledge and manage and deliver a baby properly.”---Dr. Beatrice Tucker 1897-1984.

It’s a shame there isn't a Nobel Prize for Obstetrics. What could be more important than bringing new life into the world? Without new life, there would be no humanity. None of our human accomplishments, whether for good or for ill would be possible.

But if there were a Nobel Prize for Obstetrics, Dr. Beatrice “Tucks” Tucker(photo on right) and her longtime partner Dr. Harry “Bennie” Benaron would have won one as leaders of the Chicago Maternity Center.

The Chicago Maternity Center grew out of the Maxwell Street Dispensary founded in 1895 by Dr. Joseph DeLee to provide free obstetrical care for indigent women while training doctors in the latest methods of safe delivery. Financial problems caused to DeLee to reorganize the Dispensary in 1931 and rename it the Chicago Maternity Center. From 1932 until its doors closed in 1973, the Chicago Maternity Center was one of finest obstetrical facilities on the planet.

Specializing in home births, its record of live births and live moms set a standard for delivering babies that can still surprise those unfamiliar with its work. Given that the USA now has one of the worst infant and maternal death rates in the developed world, maybe it’s time to step into the WayBack Machine and see how Drs. Tucker and Benaron got the job done.

The Chicago Maternity Center was not located on the grounds of a prestigious medical school like Harvard, Johns Hopkins or University of Chicago. It was not a wing of a world famous hospital or a clinic like Mayo, the Cleveland Clinic or Mt. Sinai. Instead the Maternity Center was located at 1336 South Newberry Street in the heart of Chicago’s West Side. When Dr. Beatrice Tucker became the Maternity Center director in 1932, West Side Chicago was a desperately poor immigrant working class community.

The diseases of urban poverty like tuberculosis, anemia, rickets, & syphilis stalked the lives of the residents. Housing was miserably hot in the summer and icy cold in the winter. There was unemployment, labor exploitation, malnutrition, street violence and domestic abuse. All of this combined into a perfect storm of mental and physical stress to further weaken human immune systems. Yet the dogged physicians, interns and nurses of the Center who went into these homes to deliver babies had better success rates than some of the finest private hospitals. Tucker respected the competent midwives and doctors that she met in the course of her work in the Chicago slums, but was contemptuous of those who did not share her passion for constant improvement. All patients deserved only the best.

West Side Chicago 1930's

What was Dr. Beatrice Tucker doing differently in what science writer Paul DeKruif called the “Fight for Life” against the “mother murderers” of childbed fever, eclampsia and sudden hemorrhaging? To understand that one must know something about her personal and professional background.

Beatrice Tucker was born in 1897 to a family with a rebel father who practiced medicine without a license, quite competently according to Tucker. The family moved frequently, as the dad, armed with his medical books, managed to stay one step ahead of the various medical boards. From the age of six Tucker knew she wanted to be a doctor, a line of work where women were not welcome. With the active encouragement of her father, she entered Bradley University in Peoria, finished her B.S. at the University of Chicago and her MD from Chicago’s Rush University.

After working in both private practice and in public health, she decided to pursue her longtime interest in obstetrics at the age of 35. She was accepted into Dr Joseph DeLee’s obstetrics program at the Chicago Lying-in Hospital. DeLee was probably the most well known obstetrician in the field. DeLee accepted 12 students and after their basic training, chose one of them for a 3 year residency program. DeLee was a lonely and contradictory man, a Jew in a country rife with anti-semitism, a political conservative, but one who when questioned about the economics of maternal care would answer,”I will say only this: nothing compares in value with human life.”

Early in her training, DeLee told Tucker about his dislike of women in obstetrics and pointedly reminded her that she was the first in his program. He once made an insulting remark about her behind her back. Undeterred Tucker confronted him:

“You shouldn’t have talked like that. You don’t know what I can do...and until you do, you should not make any remarks in front of anybody.”

DeLee was a fierce critic of the poor state of obstetrics and was not popular with the medical establishment. He knew that general hospitals were places where the presence of disease microbes made birth dangerous and he advocated specialized maternity hospitals. DeLee also believed in increased physician intervention into the birth process and was opposed to midwifery. Yet, he thought that poor women should have the best possible care when giving birth and opened the Maxwell Street Dispensary for that purpose. In 1931, when the University of Chicago ended its financial support, he spent his own funds to keep it open and renamed it the Chicago Maternity Center.

Although he preferred maternity hospitals, he recognized that home birth was the only realistic option for Chicago’s most impoverished. When Tucker had finished her residency DeLee convinced her to work at the Chicago Maternity Center by telling her this:

“Just because you’ve had three year’s training in obstetrics doesn’t mean you know it. If you go to the Maternity Center you will learn more about obstetrics and become a really fine specialist.”

Overcoming his general misogyny and recognizing her talent, he made her director of the Center in 1932. It is a sad fact that some of the most important advances in medical knowledge have been made in wartime. Under the class war conditions of Depression Era Chicago, this was true in the obstetrical “Fight for Life” as well.

Chicago Maternity Center on Newberry Street

In the depths of the Great Depression Dr. Tucker, along with her partner Dr. Benaron, developed the procedures that made the Center so successful. Using medical students, residents and nurses, they ran a combination of a clinic and a real life school of obstetrics. Students from Chicago-areas hospitals like Wesley, Memorial and Northwestern would come to the Center to do home births and learn about obstetrics on the front lines. Documentary filmmaker Pare Lorentz made a highly dramatized film about The Maternity Center in 1940 called The Fight for Life" based on the book by Paul DeKruif of the same name. Although she is listed as a consultant, no actress played Dr. Tucker in the film. Nobel Prize winning writer John Steinbeck worked on the script but was not credited.

http://youtu.be/0UW1-KfgIz4

The Film "The Fight for Life based on the book by Paul DeKruif

The Center had meticulous pre-natal procedures. When a woman came in for the first time, she was interviewed extensively and a baseline established for her general health. Her blood pressure and urine were tested for anomalies. She was advised to return to the Center on a regular basis and given nutritional and other instructions for maternal health. If she failed to show for an appointment, Center health workers would visit her at home. If there were any deviations in her baseline health, she was immediately counseled on her options. If necessary, she was taken to a hospital for a therapeutic abortion.

The health workers of the Maternity Center made themselves available day and night to all indigent patients, even ones who had not registered with the Center. For the docs and nurses still in training, this meant nerve jangling emergency cases where the margin of life and death could be minutes, even seconds. Tucker and Benaron were always on call for the complex ones and if the Center couldn’t handle them, it meant a trip to the hospital where Center workers would check on the woman’s condition and follow up on her.

But of course in the “Fight for Life”, death will sometimes win the battle. The Center would then do a rigorous post-mortem of their own procedures. Center workers took meticulous notes during the course of a delivery. Center workers would go over what had happened in an almost brutal self-examination. What could have been done differently? Where were the errors? It is said that doctors get to bury their mistakes along with the bodies of the dead. The Center did not believe in burying their mistakes, but in analyzing them and recording them. For the young trainees, this could be difficult, but Tucker and Benaron knew how important this was. They had made mistakes too.

Tucker and Benaron were patient with their trainees. Benaron put it this way,

”We never bawl them out for calling us when it was not necessary. Only when they fail to call us when they should have...When we’re humiliated by one of our mistakes, Dr DeLee always tells us--in his 45 years experience-- that he’s made nearly every blunder possible in obstetrics.”--- from The Fight for Life by Paul DeKruif

Hippocrates of Ancient Greece was supposed to have told physicians,”And first do no harm...” This ancient wisdom was one of the secrets of the Center’s success.

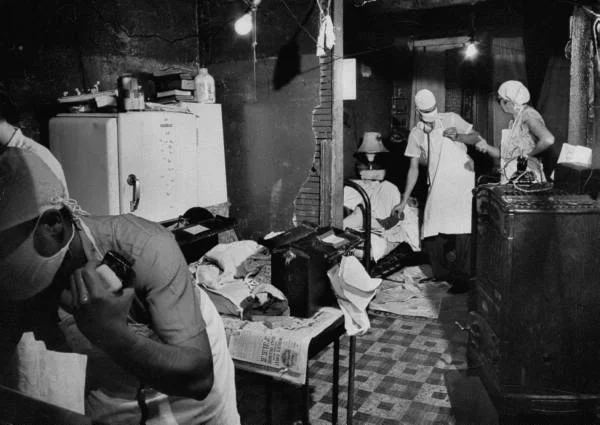

Center health workers practiced a patient vigilance and a policy of as much non-intervention with the natural birth process as possible. They would arrive with their medical bags pre-packed and ready to work. Newspapers were spread across kitchen tables as they were the most sterile table covers available. They called this the “Island of Safety.” Whether the home was neat and clean, messy and dirty didn’t matter, a small zone hostile to infectious microbes was always established.

A Chicago Maternity Center home birth

Family members boiled water so the Center workers could scrub meticulously and ferociously before putting on gloves. Then came the long waits and the note-taking as the birth process proceeded to its conclusion. Center health workers stayed with the mom for a period of time after the birth, never rushing off prematurely. Home births (except for extreme medical emergencies) had another advantage. Hospitals could be impersonal, even cruel institutions:

“My first child was born in a Chicago suburban hospital. I wonder if the people who ran the place were actually human. My lips parched and cracked, but the nurses refused to even moisten them with a damp cloth. I was left alone all night in a a labor room. I felt exactly like a trapped animal and I am sure I would have committed suicide if I had the means. Never have I needed someone, anyone, as desperately as I did that night.”---From Lying-in: a history of childbirth in America by Richard and Dorothy Wertz

Women reported being tied down for hours and subjected to frightening conversations among medical workers about difficult dangerous births and being ignored when they were in pain or when they needed a hand to hold. This type of treatment poured a flood of stress hormones into a woman’s body, making the birth process more dangerous and mentally stressful than necessary. The Maternity Center’s methods allowed for a woman to have family there to support her.

Tucker and Benaron set an example of calm compassionate caring for their Center medical workers. Their patients were human beings and deserved to be treated as such. The pseudo-science of eugenics was popular among the moneyed elite before the Nazi Holocaust made those ideas unpopular. Eugenicists questioned why any money or resources should be directed to the "subhuman" population who lived in the urban slums of cities like Chicago.The Center had no use for those ugly racist, class biased ideas. All patients deserved respect and all life was sacred. Period.

Chicago Maternity Center home birth

An example of this was a difficult case the Center had on a frigid winter morning described by De Kruif in his bookThe Fight for Life. A young black woman had given birth to a baby who was not breathing. The two young residents took the baby to another room to clear it’s windpipe of any foreign material and to blow the breath of life into it. After 15 minutes, success! Then the nurse arrived to tell them the woman was lying a pool of blood; hemorrhage had set in.

A quick call to the Center gets Tucker and Benaron on the case. After quickly introducing himself to the frightened father, Benaron collected blood from the dad and rushed to the lab to see if the dad’s blood-type matched the mom in case there was need of a transfusion. Tucker injected glucose and salt into the woman’s veins and her blood pressure rose and her vitals looked better. The bleeding had stopped.

Then as Tucker looked at the woman’s eyes, she saw them change to a vacant stare. The pulse was almost gone. It was time for an emergency transfusion, but Tucker couldn’t find the vein because the woman’s blood pressure was so low. She took a scalpel, and exposed the vein. The husband’s life-giving blood was pumped into her body. The mother began to speak:

“'Doctor! Save me! Save me for my babies!’ And then more faintly, you won’t let me die?’ These are the last words of this Negro woman who fought hanging on to harder and harder breathing. hoping her man’s blood might save her.’”

Benaron later said:

“When you hear a woman say that, you die too. Yes, she died. When we realized she was finally dead, Tucker and I dropped our instruments and began crying. The intern and the medical student and the nurse couldn’t keep their eyes dry either. We all just sat there and couldn’t stop crying.”

At the end of the record of pages for all the women who came to the Center was a message to the medical workers, “Tell what you might have done better and what to do next time”. The two young men who had saved the woman’s baby had left the mom alone for too long. They learned a harsh heartbreaking lesson. From them Tucker and Benaron learned to improve their communication to Center medical workers. By 1938, the Center had a safety record for hemorrhaging deaths 10 times better than the national average.

With such a outstanding medical record, you might think that the Center received generous funding. You would be wrong. For years Dr. Tucker lived in the Center’s basement, at the mercy of Chicago’s weather extremes. There were bugs and rodents. DeLee had been a skillful fundraiser and she learned from him how to wheedle donations out of wealthy patrons. With donations in kind and as well as actual money, she was able to keep the Center alive, but dependent on medical schools for trainees. Still, there was medical equipment beyond the reach of the Center’s finances, equipment which could have saved more lives.

But by the 1960’s, home births attended by the Chicago Maternity Center were declining. The reasons for that were complex. Medical schools were losing interest in home births and began cutting off the flow of students. Midwifery was outlawed in Illinois. The underlying reason for the decline was economics. The home birth methods deployed by Dr. Tucker were not profitable. Her non-intervention into the birth process unless absolutely necessary meant long periods of medical workers sitting and observing. Medical care was becoming more corporatized with investments in buildings and equipment. Hospitals needed patients and home births meant empty beds. Medical intervention in the form of C-sections and other procedures increased dramatically. These brought in money whether or not they were medically necessary.

In 1972, a consortium of Chicago hospitals announced plans for the Prentiss Women’s Hospital along Chicago’s Lakefront. Chicago Maternity Center supporters were worried. The same hospitals that had cut back staff for the Maternity Center were involved in planning Prentiss. The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union(CWLU) along with concerned community groups, medical activists and Dr. Tucker organized Women Act to Control Healthcare(WATCH) to save the Chicago Maternity Center. They held press conferences, attended Board meetings, and organized demonstrations. CWLU members Jennie Rohrer and Sue Davenport joined Kartemquin films to make a documentary to help save the Center.

Chicago Maternity Center Board members, most of whom were allied with powerful corporate families, insisted that the Center would be moved into Prentiss and that home births would be supported. They lied. The Chicago Maternity Center’s home birthing program was ended in 1973. The medical-industrial complex succeeded in destroying one of the finest birthing programs in the entire USA. Unlike Tucks and Bennie, life was not sacred to them---only money.

Kartemquin finished the film too late to help save the Center, but their classic documentary The Chicago Maternity Center Story explains both the history and the economics in vivid detail. I strongly recommend that anyone interested in birth and obstetrics view it. It is now available on DVD.

Dr. Tucker went into private practice until Dr. Benaron died in 1975. Tucker continued doing more home births, including the first child of two of my oldest friends in Chicago. She worked in public health and was a passionate activist for reproductive rights. You can see an interview with her late in her life as an extra feature on the The Chicago Maternity Center Story DVD. She was a great story teller with a lifetime worth of wit and wisdom. Tucker died just short of her 87th birthday in 1984.

Today a gleaming ultra-modern medical complex overlooks the Eisenhower Expressway not far from where the Chicago Maternity Center dispatched its medical workers. The Illinois Medical District is the largest medical center in the USA. Its gleaming towers are a testament to corporate medicine in all of its glory. You can take the Pink Line of the CTA from downtown Chicago and be there in a few minutes.

Just a short distance away from the Illinois Medical District are Chicago neighborhoods where the maternal and infant death rates are worse than in some 3rd World countries. There seems to be a historical amnesia about the medical advances that the Chicago Maternity Center made in its Fight for Life. Corporate profit has triumphed over the deeply personal and highly effective medical procedures practiced and taught by Dr. Tucker.

I was one of the nurses that worked there. I became familiar with the center as a student nurse and was employed there after graduating from nursing school. Dr. Tucker was a remarkable individual that truly believed in birth as a natural process, that involved the family as an integral part of the birthing experience. Birth was an incredible miracle not with the wailing, drugs and paternalism of the hospital experience that I saw in my OB experience. As a young nurse it was remarkable and as a young woman an eye opener to the beauty and miracle of birth. Thank you, Maternity Center and Dr. Beatrice Tucker.----Mary Amari RN

Dr. Beatrice Tucker left us a legacy that cannot be measured in money because it represents the highest aspirations of the human spirit. It’s time we reclaimed that legacy and put it to work. Today.

Dr. Beatrice Tucker

Sources Consulted

The Fight for Life by Paul DeKruif 1938 (Book)

The Fight for Life 1940 (Film)

“Recollections: An Interview with Dr. Beatrice Tucker” by Diane Redleaf & Pat Kelleher from Health and Medicine, Winter/Spring 1983

Maternal Mortality of the Chicago Maternity Center by Beatrice E. Tucker, M.D., AND Harry B. Benaron, M.D. from the American Journal of Public Health, January 1939

Medicine: The Baby Commandos from Time Magazine (1954)

Birth on the Kitchen Table from Life Magazine (1972)

WATCH Demands by Women Act To Control Healthcare (1972)

The Chicago Maternity Center: 77 Years of home deliveries from Womankind (1972)

Lying-in: a history of childbirth in America by Richard and Dorothy Wertz (1989)

The Chicago Maternity Center Story by Jenny Rohrer, Sue Davenport and Gordon Quinn 1976 (Film)

Tucks by Leon Carrow (2007)

Fortnight on Maxwell Street by David Kerns (forthcoming novel about the Chicago Maternity Center)

ORIGINALLY POSTED TO BOBBOSPHERE ON WED FEB 29, 2012 AT 10:21 AM PST.

ALSO REPUBLISHED BY PROGRESSIVE FRIENDS OF THE LIBRARY NEWSLETTER AND COMMUNITY SPOTLIGHT.