by Jeanne Galatzer-Levy "I was really adrift, but I wanted to do something, and it seemed to me that if you were going pick something in terms of women and politics the front lines was abortion because women were dying and that was real."

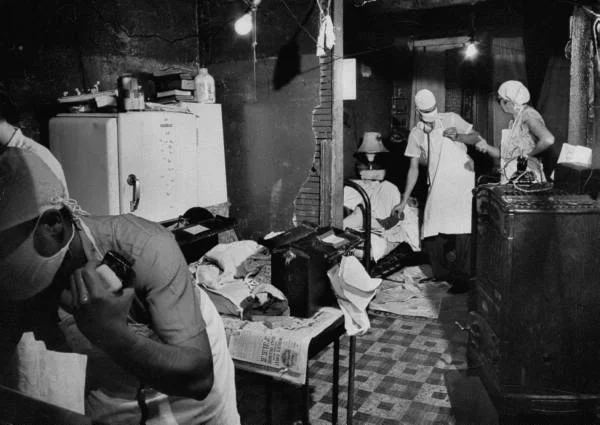

(Editor's Note: This article was developed from a 1999 interview conducted by Becky Kluchin. Jane was the CWLU affiliated underground abortion group. The picture of Jeanne was taken during her Jane days.

"I was really adrift, but I wanted to do something, and it seemed to me that if you were going pick something in terms of women and politics the front lines was abortion because women were dying and that was real." -Former Jane volunteer Jeanne Galatzer-Levy

What was Jane?

Jane was the abortion counseling service affiliated with the CWLU. Before abortion was legalized in 1973, Jane members, none of whom were physicians, performed over 11,000 illegal abortions. Their philosophy was that women had the right to safe humane abortions and that if this wasn’t legally possible , than it was up to the women’s liberation movement to take up the slack. Jane took its medical and social responsibilities seriously, so careful training and a humane relationship with their clientele were an important part of the Jane experience. Known officially as the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation, "Jane" was the name people would ask for when they first made contact.

Jeanne Galatzer-Levy joins Jane

Twenty year old Jeannne Galatzer-Levy’s introduction to the Abortion Counseling Service came at a meeting in Hyde Park. It was a rocky start. She had brought a friend named Sheila with her, which unbeknownst to her, violated Jane’s security protocol because Sheila had not been specifically invited. After some pointed discussion, Sheila was allowed to stay, but the incident illustrated the everyday stresses of working in a clandestine abortion network.

Jeanne’s first meeting was especially tense, because a young woman who had come to Jane had recently died. She had wanted an abortion, but had such a dangerous infection that she had been urged to check into a hospital immediately. Jane attempted to follow up her case, but it took several days to determine that she had died in the hospital.

There had been a police investigation. Although the detectives were sympathetic to Jane and did not think that the Service was responsible for the woman’s death, some members had left the group over the incident. It was a difficult soul searching time for those who remained.

By the time Jeanne Galatzer-Levy joined up, Jane members were performing the actual abortions themselves, based on the techniques they had learned from “Mike”, the male abortionist with whom they had formed an often contradictory, but very close relationship.

Jeanne remembers her first orientation,

It was a very large meeting, there must have been 30-35 people, all in the living room that was probably the size of my dining room, you know a big living room, a big old Hyde Park apartment, but still, a lot of women and we’re all sitting on the floor and a few in the chairs in the back that had been pushed to the wall. Then we were kinda told what the Service was. And you know, it was pretty straight forward, I think. They pretty much told us everything except they were doing it themselves.

They told us they weren’t using doctors anymore, and the history of that. My friend Sheila who was so much more perceptive than me, figured out immediately that they were doing it themselves and who it was that was doing it. Sheila’s very sharp. But I was completely oblivious. And we joined.

And that was how we started. And I was paired—we got big sisters— and what we did then was, at the end of a meeting they actually brought out the cards and passed them around and people took cards, but not us, we didn’t take cards. Then I met with Benita in her apartment a couple of times and just went through what we were gonna do and what not, and then she set up a counseling session and I actually sat in on it.

The cards that Jeanne Galatzer-Levy is referring to were the index cards Jane used to assign abortion clients to the Jane volunteers. Cards were passed around at meetings. People tended to want the “easy” cases and the “difficult” cards usually ended up being dealt last. Short term abortions were usually easier cases, so volunteers would start out on them. Long term abortions were more complicated and so demanded more counseling experience.

Galatzer explains,

The cards would go around, and everyone would grab you know, the one who lived in Hyde Park and was twenty years old and was three weeks since the last period, because , it was obviously gonna be better. And then there would be the woman in Long Grove who it had taken two months for her to find us, and she would go around and finally someone would say, we’ve gotta get rid of this woman, and someone would volunteer and take it, and I think some people learned long term counseling by saying I’ve never done one but I’ll do it if you help me.

Jane always tried to do follow up after an abortion was performed, but the results varied considerably:

I mean some people you really got to know and you really had these wonderful relationships with, and some people you just felt there were these huge walls around them and there were walls around you. You just touched at this one point and you helped them and you know that was it, and you knew that you were never gonna see them again. That the one thing in the world they wanted to do was to forget that this had ever happened.

According to Galatzer, the people who had short term abortions were most likely to disappear as the procedure was less prone to complications. With long term abortions, follow-up was a necessity:

The long terms, you induced an abortion, you induced a miscarriage. You had to follow up. It was very important to find out what happened because what we did originally, there was a period when we had Leunbach paste and all these other things, but originally what we did was we broke the bag of water, and they pushed out a much of the amniotic fluid as they could, and the fetus would die, and then they would go into a miscarriage. But things can go wrong with that.

One, you compromise the integrity of the uterus, so there’s a real possibility of infection, which there is with any natural miscarriage too. You could’ve missed and the baby could live, it could still live, and then you’d have to do it again. The body might not go into a miscarriage, and then there’d be dead matter in the uterus— mostly it worked very well, but there were a lot of things that could go wrong, and so it was very important to find out, to follow them, to find out whether they’d gone into a miscarriage, and then find out what happened.

Once they were in a miscarriage they were urged to go to the hospital or emergency room and then say they were in a miscarriage and deny having done anything. If they did it on their own, which some people did, they needed to have a follow up D and C, to do that because you can’t leave anything hanging around in there, nothing. So you did have to really follow them. It was a very different kind of thing. And you had to, it was kinda hard because you really had to establish that relationship. You couldn’t let them slide because you couldn’t pretend that it wasn’t happening the way you could let somebody get away with that who was eight weeks pregnant and it was gonna be something they’d deal with a lot later. It was a different situation.

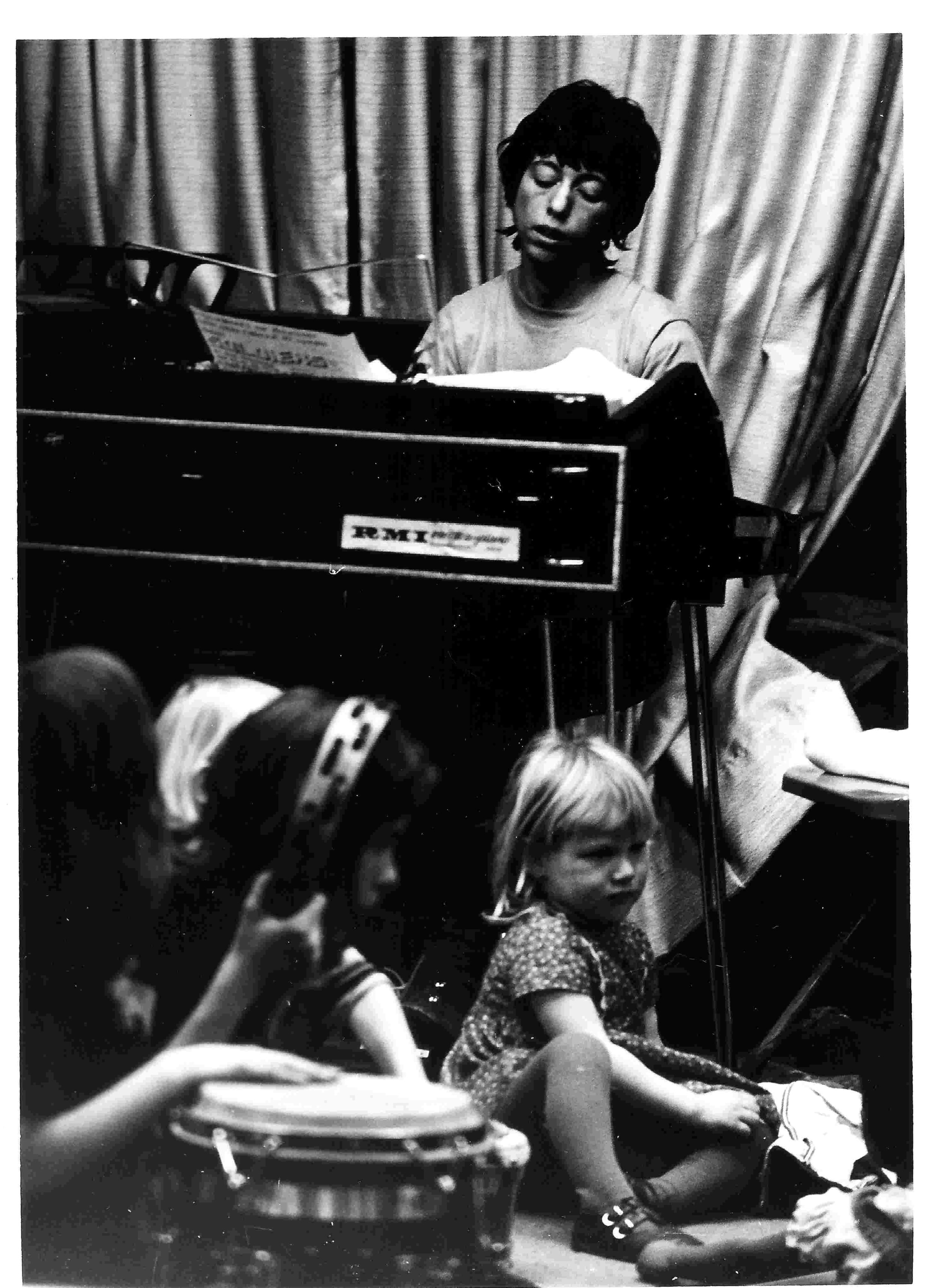

New volunteers usually started out working at the "Front" which is what Jane called the apartment they used as a reception area. The abortions were performed at another apartment called, "The Place". Women were encouraged to bring along people for emotional support, so the "Fronts" became a gathering place where men, women and children could all be found.

Jane volunteers who worked the "Front", kept everything on schedule, gave out information and reassurance, inventoried supplies and served food and drinks. One Jane volunteer remembers that food was one of the few things that Jane ever really splurged on. Drivers would take a few women at a time from the "Front" to the "Place" and then back again when the abortions were done.

Jeanne Galatzer-Levy describes starting out at the "Front":

Everybody was expected to work the Front, and it was a really long day, and it was hard. People would come and their significant others of some sort or another, their sisters or aunts or cousins or boyfriends or whatever would come, and we were very woman centered. We had all this food at the Front. We always had all this food and tea and soda and things like that. And we gave out—we started them on a dose of tetracycline. And gave them a box of pills that included ergotrate and tetracycline. They took these afterwards, to contract the uterus and help them get back into shape.

You would talk to people. They’d be nervous and then the people who were going for the abortions would be driven off and their significant cousins, brothers, sisters, children whatever would then be sitting there. And so you would have to kinda entertain them. And you know, I was a fairly shy person and it was hard, you know it’s kinda hard to be conducive to strangers in this very peculiar circumstance. I was very young, and you were giving a kind of tea party all day long, and you really were kinda out of the loop, you really didn’t know exactly what was going on. So first you did that. And I did that for a while. And then there was the driver and I moved very quickly into driving because I was one of the few people who had a driver’s license. Lots of people didn’t have their license. Well U of C at the time was full of New Yorkers and New Yorkers don’t drive, like I was one of the people who helped teach Sheila how to drive.

After abortion became legal in New York, women with more money could hop on a plane and have the procedure done legally, so Jane’s clientele became poorer. Jeanne Galatzer-Levy was treasurer at that point and describes Jane’s finances,

Our population became much poorer and we charged, at that point one hundred dollars and we took anything—we literally took nothing. We asked that they give us something. But often they didn’t, you know. We were averaging about fifty bucks. I was by then the treasurer and we were averaging about fifty bucks which we figured we could do, we had figured out that whatever we charged we ended up with about half that per.

I think earlier on, when we were using ‘Mike’ we had to actually have the money and then he’d give us a few free ones. People have wonderful stories about getting people’s coin jars. I never got that as a driver, but I did get a lot of singles. And I, the driver would pick people up, drive around a little bit then go off onto a side street, park the car and ask for the money. People would hand me the money and I would take it, and then I would shove it into my pocket. I never counted it. And I don’t think anybody ever counted it.

So you know, I didn’t know what people handed me and I didn’t care. And sometimes they would say when they handed me, I don’t have all this, and I would say it doesn’t matter. So we did have some really broke women, and for some of them, I mean they’d been lied to by their boyfriends, they’d been lied to by everybody and they had never really asserted themselves in any way, shape or form, and this was their decision not to be in this position, not to have a baby, not to get stuck again. And they were really flying. They would be really excited you know? We were real sunny and happy, so you know, they allowed themselves to be.

On May 3, 1972 Jeanne Galatzer was working the "Front", caring for three children that had been left by one of the women who was getting her abortion at the "Place". What Jeanne didn’t know was that the police were already raiding the South Shore apartment that was serving as the "Place". Ruth Surgal had just dropped off some snacks at the "Front" and when Galatzer heard a knock on the door, she assumed Ruth had forgotten something. It wasn’t Surgal, but a large beefy Chicago detective. Jane was being busted at both locations.

The Abortion 7 Bust

"We were terrified. We were looking at like one hundred ten years, one to ten each count. It was very impressive." -Jeanne Galatzer-Levy

Jeanne recalls what happened when she heard the knock at the door:

I was at the Front which was an apartment in Hyde Park. It was a nice apartment. It was a ground floor, and it had this long, long hallway, and we were way at the back of this building. Ruth had been over, dropping off food or something, and there were a bunch of people there, and I had been talking to them. It turns out that I had a long, very sincere talk with the woman who had turned us in, which really pissed me off later. I didn’t know, I mean of course I didn’t know. But she was having ambivalent feelings about it, so I was really very helpful. Later I wanted to kill her I was so pissed off.

I opened the door and there were the tallest men I had ever seen in my life, in these suits, and you knew immediately what this was. I don’t know if I said anything or if they said anything.

I think they announced they were the police, and I turned around and walked in front of them and said, "These are the police. You don’t have to tell them anything." And they were really irritated. That was how they decided to arrest me, because I’d opened the door, and you know, it was perfectly obvious to me— I’m a control freak you know, and I think I took charge the way people do.

They were really tall! Really weird. I developed this whole theory. I love crackpot theories, I intend to be a crackpot when I grow up. My theory is that you had to be really tall to be a homicide cop. These were homicide cops, because abortion was a homicide. And they were homicide cops who hated being there. You know it’s not easy to make homicide detective. You really have to be good. It’s not even political like taking the sergeants exam. You really have to do something, and they do it because they want to. And by and large what do is they track down people who kill other people. And they think of themselves as good guys and they hated being there. This was not their kind of crime. So they were very ambivalent about it. They were very funny. So we were taken, I was taken, the whole group of us were taken down to the station. I wasn’t handcuffed, I don’t think. I was treated very nicely, except that I was in a state of perfect terror.

They took everybody. We were dealing with a very poor population, so if a woman was on her second pregnancy and she had a two year old, she had nobody to leave that two year old with. We would beg people, if you’re gonna bring your two year old bring your sister to watch the two year old. But we had children running around, aunts, cousins, uncles, friends, a random bunch of people.

There were men at the Front and they took them too. I don’t think there were a lot of men, but there were a couple. You know I think they were teenagers, very young men. And they tried to sort us all out, and then they interviewed each of us.They asked us questions, and we said—you know we were really middle class savvy people, and we all said, "I don’t have to answer that." And basically, at the end of the day I think that they picked who they arrested on the basis of the ones who said, "‘I don’t have to answer that. You know, because everybody else was talking."

Actually some of the women just wouldn’t say anything. But when we hired Joanne, the attorney who defended us and she got the paperwork, she said, "You’re the best clients I ever had, people talk to the police all the time and you guys didn’t, I love you." We knew we didn’t have to talk to the police and we didn’t.

They asked us,"How much do you charge?" We said, "‘Well how much do they say we charged?". And they would go crazy because they’d ask the women,"Well what did you pay?" And somebody’d say twenty bucks and somebody’d say one hundred bucks, and it didn’t make any sense at all. There was usually this huge wad of cash in illegal abortion busts and the women would come in and say," I paid five hundred dollars." When we got busted, there was a wad of cash, but it was all singles, and these women were saying, "Oh I paid ten dollars."

We were very self-aware I think, and there were all kinds of class and race things going on with the police.They felt more like us then like the women they were supposedly protecting from us, and they kinda wanted that relationship. So that was bizarre, just bizarre.

Martha was in the middle of her period, and she needed a tampon, she’d been asking everybody and was getting nowhere, and a woman policemen walked by and Martha just spontaneously jumped out and called to her. Perps can’t act like that. It was really scary because it made us realize, you know, who were the arrested. What was a very natural act for her, was really inappropriate in that situation. It was very scary.

We weren’t questioned at the 11th and State lockup, we were questioned at wherever the hell it is, the local. And then we were put in paddy wagons, which are really unpleasant, and driven to 11th and State, and the drive in the paddy wagon was a riot. It was all women and of course everybody else who was arrested was a hooker, because that’s all they arrested women for then. And one woman was just giving hilarious stories, regaling us with stories of the street. It was really quite funny. And then we were in the women’s lockup at 11th and State.

We were a big group. People said to me afterwards, "Weren’t you scared?" But once we were together as a group I wasn’t scared again. But it was very unpleasant, a very unpleasant experience. You just, don’t have choices. It’s very strange; it’s just not the way life is. Very unpleasant. But we were together, and we were a group, and we figured something would happen. One of the women who was arrested, had a husband who was a lawyer. And he had managed to communicate to her. People were calling for us. We’d each made a phone call I guess. We knew that things were happening, and that they were going to pay the bail, and then there was the question of whether they could get us out that night or whether we’d have to wait until the morning.

Later into the evening, they put us into double cells, but we were in a row so we could talk to each other. I was put into a cell with Judy who was nursing at the time and they managed to get her out because she was nursing. She really wanted to get out, she really did. Her son really needed her to get out and her husband really needed her to get out too. If she we got her out on her own recognizance, that would lower the bail on all of us.

So they got her out on her own recognizance that night, at night court, so then I spent the actual night alone. But it was next door to other people. It was very unpleasant.In the morning, they gave us bologna sandwiches, which I couldn’t eat, and coffee. It was awful, but that was breakfast at Cook County Jail. Then they loaded us again and we went to, 25th and California, and we went into the women’s lockup there, I guess it could’ve have gotten much worse because women now are much more commonly arrested for all sorts of wonderful things. But at the time, many, many fewer women were arrested . The men’s lockup was horrible at 25th and California, I’m told, but the women’s lock up was pretty small and we were a pretty large group.Then we were called in front of the judge who was very nasty, but who let us out on bail to the arms of our waiting whatevers.

I called my mom and told her that my name was going to be in the paper, and she hadn’t seen it. I don’t think it had occurred to her to scroll down and look for my name. And she was very upset. She wanted me to promise that,"I’d never do anything like that again, and it was very nice but, I understand that you believe in this but you’ll never do this again will you?. You have to be careful," and all the things that mothers say.

I now appreciate that more than I did then. She was very frightened, and she didn’t like it, and we had a conversation about that. But I wasn’t living at home and that was that. And honestly my closest friends were in Jane, so the question of how I dealt with it was really in the context of those people, not in any other context.

After the Bust

Eventually the "Abortion 7" as they came to be called, were charged with eleven counts of abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion. According to Galatzer, the remaining members of the Service who had not been arrested distanced themselves from the Abortion 7. Galatzer herself is unsure why this happened.

According to Laura Kaplan, who wrote The Story of Jane, part of the reason was the fear that since the police would be watching the "Abortion 7" people, their continued association could endanger the work of the Service. Some members wanted to shut down the Service, but the leadership insisted on continuing. There were desperate women out there and they needed abortions. Whatever the reasons, Jeanne Galatzer-Levy found the distancing painful and upsetting.

Jeanne recalls:

We were terrified. We were looking at like one hundred ten years, one to ten each count. It was very impressive. We were terrified and we all quit the Service, in fact the group withdrew from us and reconstituted and did their own thing. It was like they really didn’t want to be contaminated, which was also very, very upsetting for us. Though luckily for me, my friends were in the group who got arrested.

We became a group, and the first thing we had to do, was meet together and try to deal with the fact that we were in big trouble.We really tried to talk to each other, and that was difficult. We were a very disparate group. You could not have done a better job of getting us swiped across the demographics. You really couldn’t have. We went from Abby who’s really, extraordinarily bourgeois. She and her husband were living out in Downers Grove which is an affluent suburb of Chicago and she was a New York intellectual political person who had sought us out as a political thing and was really very, sorta old left kinda thing, but very bourgeois.

And then there was me at the other end—and Diane, Diane and I were both dropouts so that was the demographics. It went from one end to the other. Sheila was gonna start her senior year. Martha and then Madeleine were housewives with children,-young children. Judy had just had her first child; she had been a high school teacher. I think she had just retired, or taken a year off.

Madeleine who was very involved with NOW, and very involved with much more mainstream kinds of things, had also been very involved in La Leche League. Martha and Madeleine had both been involved in La Leche League early on because they’d nursed. They nursed when nobody did, you know, a million years ago. I don’t think we were endorsed by La Leche League, but you know, they’re great people. And in some ways, we had trouble becoming a group, and in some ways we never did. But we did have a common interest, and the first thing we did was we interview lawyers, and that was really fun. I mean, everything we did was fun, we just had a good time because, we’re just who we are.

We’d go downtown we’d all get gussied up, and it really was a matter of gussying up because frankly we all looked like that scene from The Snapper. It’s an Irish movie, one of the rowdy "down home on the soil " movies. The teenage daughter becomes pregnant, so it’s this whole thing of who did it to his daughter you know. She’s the oldest child of this large family. In the end, she has the baby and they all go to see her and the whole family dresses up right, meaning the father puts on a suit and the mother puts on a kind of a nice dress, and the little girl puts on her baton twirling outfit because that’s the nicest thing she’s got and the little boys got a superman shirt And I thought that’s exactly the way my family always gets dressed up. I loved it because it looked like my family.

Well, when we went to interview the lawyers, we looked the same way...we’d all get gussied up. But except for Abby, we were clueless as to how to do that. We didn’t have those kinds of clothes anyways, except for Abby of course. So we’d get all gussied up and we’d go down and we’d interview somebody. It was a very high profile case, and defense lawyers really like big high profile cases because they get their names in the newspaper and any publicity’s good publicity, believe me.

Defense lawyers as a group, and I say this knowing one of my closest friends is a defense lawyer and is actually very, very good, are a slimy bunch. There’s’s a lot of money in it, and you deal with some pretty sicky people, and some of these people are really pretty creepy. So we’d meet people who were really creepy.

One guy, I can’t remember his name, a very big guy at the time, had this office, this huge room with a huge desk in the corner of his office, and it was gleaming mahogany desk with, and you know he’s got this couch area. The first thing out of his mouth was, "You know you could be in trouble with the taxes". Because you know it was clear we earned money. But this had not occurred to us at all, you know, boy that was the last thing we were worried about.We said,"Not him. No way."

So we’d interview various people then we’d all go out to lunch. And that was all I was doing at the time. And it was pretty much all Sheila was doing at the time. She was trying to finish school, which she did, stretching though that summer. And she wasn’t sure what she was gonna do or, it was very up in the air. Some of us had things that don’t go away like, Martha’s kids, they didn’t disappear for the event. So she’d get up every morning and take care of the kids while all this was going on.

So we interviewed people and we ended up with Joanne who was a gasp. She was just a gasp. She really had this sorta hard as nails persona, and she was just a riot. She had been an elephant girl in the circus. She was great. She’d run off and joined the circus you know, a really interesting person. And she really wanted the case, because she was a woman and she thought a woman should handle the case, and we always thought that too. There were a lot fewer women lawyers then, it was a lot bigger deal. And we liked her. She was the only one who really spoke to us politically.

Well actually, we did talk to a law classics guy, who, I think Northwestern’s legal department. He was very political. And he scared the shit out of us because he was much more interested in the political aspect of it than what happened to us. And the last thing any of us wanted to do was to spend any more time in jail ever, and be martyrs. And we did run into people who had weird ideas about what we could mean to them. That were very strange. We just all quickly agreed that we had no interest in that. We had no interest in it being a political statement, we just wanted it to go away. What we were doing was a political statement, but going to jail was not one we wanted and it wouldn’t help anybody.

Through most of the first three or four months nobody in the Seven went back to work for the Service. And then Diane came in to a meeting and said,"‘I’m going back to work…this is really what I want to do, I really care about it, I was just on the verge of being trained and I really wanna do that, and I’m going back." And then Martha went back and I went back, and then Madeleine went back. Abby did not, and hated it that we did. Sheila didn’t because she wanted to get on with her life, she was going back to school and thinking about what she wanted to do. I don’t think Judy went back to work, and I don’t remember why.

Why did I make that choice? Well it’s very interesting. I was twenty-one when we got arrested, and quite frankly it had never occurred to me that we could get arrested. And probably, it had never occurred to me that choices had consequences, that actions have consequences. There’s nothing like a night in Cook Country Jail to make you realize that actions have consequences. It was an enormous growth experience for me. In a way I was really sorta shaken out of my little cocoon of being a kid. I really realized that what I did made a difference,and could have real consequences and I had to really think through this decision. When I talked through why I was doing this, I wanted to be doing it still. Which made me feel real good about having done it in the first place, and I decided well if this is what I want do then I should do it. Its sorta a civil disobedience argument.

The level of seriousness changed enormously. I was blithe about it, clearly I thought it was important, and I wanted to do it, and I was really having a lot of fun doing it, it was really rewarding. But afterwards I realized that I had made a very serious choice and if I was going to do this, I could get into really serious trouble. And I was gonna do it anyway.

The End of Jane

Joanne, the Abortion 7’s lawyer, pursued a strategy of delay. She knew the Supreme Court was going to rule on the Roe vrs. Wade case, a major abortion test case. If the Court ruled in favor of abortion rights, then it would be easier to get the defendants off, or at least cut a better deal.

Jeanne Galatzer-Levy explains how it all ended:

Once we had hired Joanne, basically what she said was,"All we’re going to do now, from now on, is delay this until the Roe v Wade decision comes down because nobody wants to prosecute you knowing that this is happening. They don’t wanna waste the money, so they’re gonna allow us to wait." So we just diddled around. We had periodic court appearances, in which again we’d get all gussied up and we’d go down and have lunch after the court thing. And we just were waiting, and we knew it was coming.

Some of us had gone back to work, some of us hadn’t and we were just waiting. Then the decision came down and I don’t remember where I was standing when I heard this decided, I just remember that we all called each other and people called me. We got together and you know we were thrilled of course, we were real excited and happy, and you know, it was like everything else, you know you get into the court system and everything up, the arrest is so dramatic and exciting, horrifying and all those things, and then everything past that is so boring, and slow and very different kind of time frame and very different emotional thing. It’s very surreal. And disconnected in a way that the arrest is so immediate. So basically she said we’ll all go in and we’ll see, and I’ll talk to the prosecutor and see what they’ll do. Obviously they’re not gonna prosecute you at this point, but there are issues involved. So she went in and they cut a deal. They dismissed everything, and they didn’t hit us with practicing medicine without a license which they could’ve, in exchange for us not asking for our instruments back. We said okay sure.

The Abortion Counseling Service sort of ground to a halt. I think we did two more weeks. Then we had a party and it was all over.

After leaving the Abortion Counseling Service, Jeanne Galatzer-Levy joined the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective and helped produce the large colorful feminist posters the group made famous. In 1974, she married Robert Levy and over the years raised 4 sons and 1 daughter, which she describes as,"...the first, best and most important thing I will ever do."

When her children were older, she returned to school and finished an MS degree in biochemistry(1994) and a second BA in journalism(1999). She now works as a freelance science writer. Her work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune and she has just begun a project for the International Medical News Group.