Naomi Weisstein: October 13th, 1939 - March 26th, 2015

Pioneering neuroscientist

Among the initiators of the Cognitive Revolution

See her “Neural Symbolic Activity” in Science, and many other papers

Feminist

Co-founder, Chicago Westside Group (1967)

Many papers available at Chicago Women’s Liberation Union Herstory website

A sampling:

“Kirche, Kuche, Kinder as Scientific Law: Psychology Constructs the Female” (40+ reprints around the world)

“’How Can a Little Girl Like You Teach a Big Class of Men?’ and Other Adventures of a Woman in Science"

Weisstein essay in Feminist Memoir Project: “Our Gang of Four”

Rock Musician

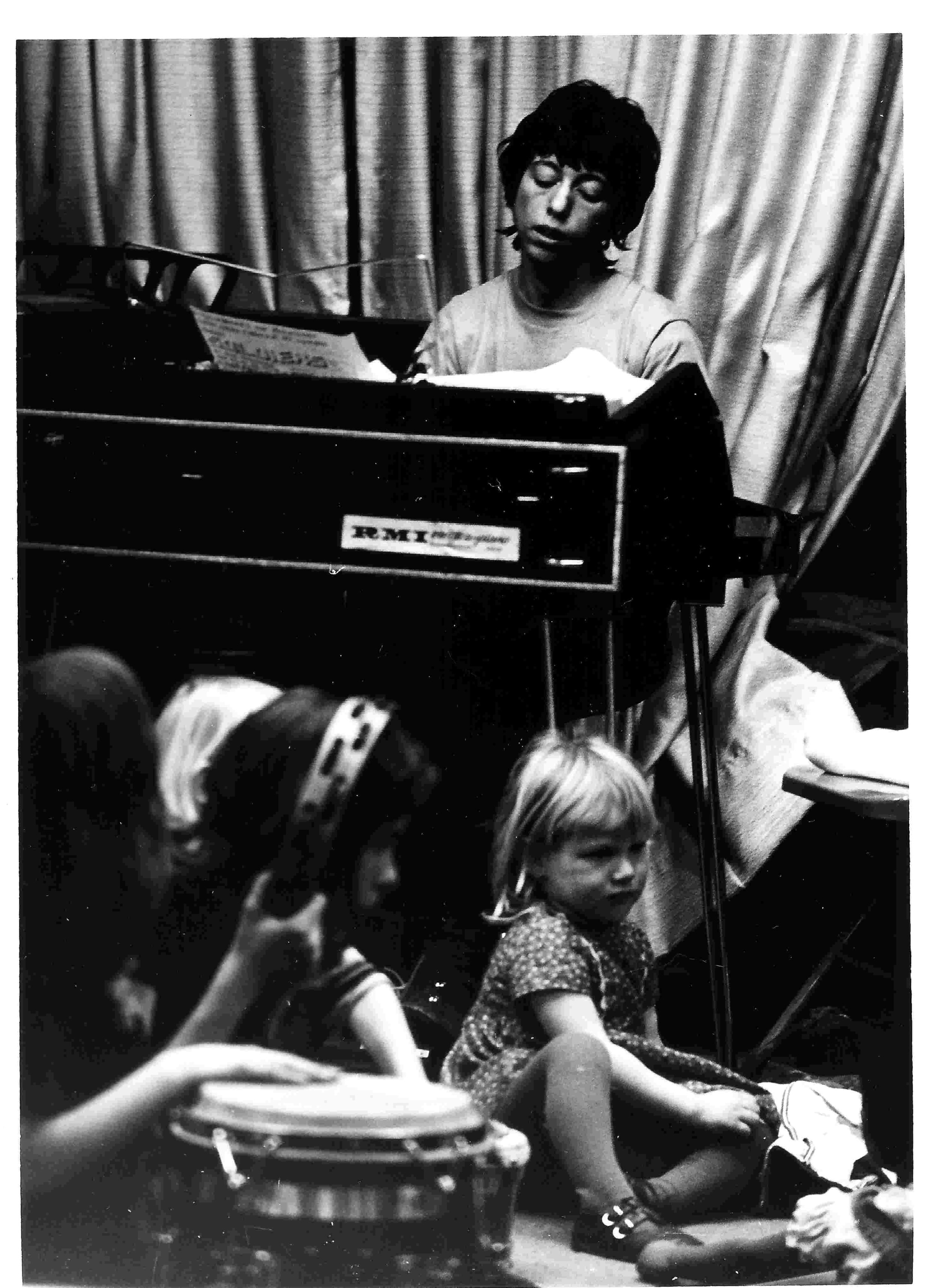

Founder of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band, 1970-73. Weisstein’s history of the band can be read at New Politics.

Brief clip of the band in Mary Dore’s film, “She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry.”

Two records: “Mountain Moving Day,””Papa, Don’t Lay that shit on me.”

Comedian

Came this close to running off with Second City in the 1960s.

Beloved Wife of Jesse Lemisch 1965-2015

“Papa don’t lay that shit on me, I ain’t your groovy chick.

Papa don’t lay that shit on me, it’s just about to make me sick.”

--Naomi Weisstein in the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band

Naomi Weisstein was a fierce warrior for justice. She was a passionate disrupter of the existing order. She was a brilliant scientist. She was a fighter for women’s liberation. She was hysterically funny. She had biting insights. She was my beloved friend.

I first met Naomi when I was a student at the University of Chicago in 1963 or 64 and she was an adjunct professor in neuro-psychology. Her national

reputation preceded her, as one of the first people in the world to help identify how memory worked in the brain. Her brilliance was apparent in almost every conversation and all she wrote. But she couldn’t become a full professor because of the so-called Nepotism Rule that said relatives of professors could not become full professors in order to avoid a conflict of interest in such appointments. Yet the Levi Brothers were able to be Dean and Professor at the same time. The issue was obviously a means of keeping women off of a tenured track and getting wives at a discount rate when husbands were recruited to be faculty.

Naomi’s husband Jesse was on a tenured track. He was a remarkable radical historian who helped teach me and so many others how history was made by the people from the bottom up. He did a major study of “Jack Tarr” a sailor in the Revolutionary War—showing how life was actually lived by the people most impacted by the history they helped to make.

So we protested the nepotism rule. And we worked together discovering and building women’s liberation voice at the University, in the city of Chicago and spread it throughout the country.

Jesse and Naomi were a remarkable couple.

They mentioned that years later when they once went to a therapist they were reminded that they were really two separate people and needed to learn how to separate. But they realized while they were separate, they also were deeply deeply connected and really did feel they were part of each other.

They were political and personal partners, in love and in shared struggle in the movement.

On meeting Naomi, I felt electrified. She has such insights, outrageous assessments, and was willing to take bold action for women and a better society.

She brought such wit to her words and actions. When she was younger she had been influenced by Lenny Bruce, the sharp witted and often caustic comedian challenging conventions and politics as usual of the 1950s. Naomi sometimes described herself as a female Lenny Bruce. But she was not an imitation anything. She was pure Naomi.

We ended up teaching what I think became the first campus women’s liberation session in the country.

Naomi and I were part of the West Side Group that may have been the first (or one of the first) women’s liberation groups in the country. We usually met at Jo Freeman’s house on the west side (therefore the name of the group). It was a remarkable and exciting group. The discussions were a bit like intellectual jazz—there was a riffing off of each other’s ideas with creativity on a common theme, often going to places that we never imagined we’d go before. And we were all made better and smarter by our working together. Among the people in the group were Amy Kesselman, Vivian Rothstein, Shulamith and Leah Firestone (for a little while), Fran Rominski and others.

We’d go from the group to create action and other groups.

Out of the effort we helped to convene the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union. A remarkable organization with both work groups (Action Committee for Decent Childcare, Liberation School, abortion counselling with JANE, organizing Janitresses in City Hall—who finally won equal pay, high school students, WITCH and much more) and home groups for discussion and consciousness raising.

After I graduated and Naomi and Jesse went to work at institutions in different cities, we lost contact with each other. Several years went by and we met in an airport by accident. We connected so deeply as if we had seen each other just the previous week. And again we connected as if we were riffing.

We co-authored an article for MS magazine called Will the Women’s Movement Survive because we were becoming deeply concerned about the increasingly individual focus of the movement, away from organizing. The movement began with the insight that the personal was political, meaning that problems we thought were ours alone were socially shared and needed a social solution. By the early 1980s this started to shift to looking at individual problems and finding individual solutions--to raise feminists read non-sexist books to your children, to spread women’s liberation be liberated in your personal dress and style--all worthwhile, but not a substitute for social and large scale action.

Again, our lives interceded and we fell out of touch.

We lived in different parts of the country and our lives were busy with other things.

In the 1980s, at an SDS reunion, I met Amy Kesselman, who told me Naomi had devastating CFIDS (Chronic Fatigue). Because of the vertigo she was on 24 hour bed rest and could not be in a room with lights very long and needed round the clock nursing care. Because of her illness, she lost motion in her feet. This very petite fire cracker, became bloated from her medication. She lost many of her teeth. Lost much of her hair. Her body was destroyed. And still her mind was sharp and her spirit resilient.

Jesse was there for her. He was there to provide care and defend her when she could not defend herself against the insurance companies, trying to kick her off their coverage; against the doctors whose treatment and often mis-treatment sometimes made her worse; against the landlord, allowing noise that was devastating to Naomi in her condition, and more.

Amy told me that she and her partner, Ginny Blaisdell, called Naomi every weekend and left a phone message for her, even though Naomi was too weak to hear the message and had it retrieved by the nursing staff or Jesse.

I followed Amy’s lead and started calling. And then visiting her every time I made a trip to New York.

Naomi was only well enough to visit for about 45 minutes and even then might need a week to recover her strength.

We kept doing this for perhaps 20 years.

By my bed, I have a shelf on a bookcase (positioned so that I see it every evening). It is filled with Naomi memorabilia, letters and gifts she sent. Warm and endearing and love filled. Rants that are filled with biting criticism, pain and anger. A blue hippopotamus from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Meerkats of many sizes and kinds. A lovely necklace. Beautiful letters.

She valued meerkats. They are animals who are fierce defenders of their families and those they care about. They stand guard and watch over them. Naomi was fierce in defense of what and who she loved and fought for them.

Naomi was often fierce in her anger and hurt. She was sometimes filled with rage. She sometimes lashed out at those close to her. She sometimes drove those who cared away.

Perhaps her fighting spirit kept her going.

Even when she was too sick to do much physically, she kept guard mentally and kept up. She wrote. She thought. Her mind and spirit so sharp even when her body was failing.

I came up when she was previously hospitalized with treatment that nearly killed her.

But still she kept on.

Then she found out she had cancer.

And intense pain.

And swelling.

She went to Lenox Hill. It was a horrible experience even with Jesse and his wonderful sisters and two nursing aides providing care.

I came up again.

We laughed and cried and told stories.

We talked about how we would have a party to celebrate when Naomi beat this illness and combine that with celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary.

Just that week I visited, a book was published reissuing the pathbreaking research Naomi wrote on aspects of how memory works and where it is located in the brain.

And we told each other how we loved each other.

Naomi said she wanted to live.

She said that if she did not survive this illness and its treatment, she wanted to be remembered for how she loved

Science, women’s liberation, Jesse and her friends.

And she wanted us to carry on.

And so we do commit—to being fierce warriors for justice. Being passionate disrupters. And remembering Naomi and we carry on with the values and the struggles that she fought and cared about throughout her life.

--Heather Booth, March 29th, 2015

Survival and Death

Naomi fell ill with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in 1980 and became completely bedridden in 1983. We fought America’s most powerful insurance companies in court and in the press (see Lemisch, “Do They Want my Wife to Die?” New York Times, April 15, 1992) and defended her 24/7 home nursing, which continued until the day of her death. Among her most heroic works are her creative articles in science and feminism, written in this period, entirely from her bed. In March 2015 she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer at New York City’s Lenox Hill Hospital. In every way possible, LH expressed ignorance and contempt for her underlying ME/CFS. (See Gina Kolata’s “Doctors Strive to do Less Harm," New York Times, February 18, 2015, which, without naming LH, fit precisely the harms committed by the institution; not a soul who I encountered at LH took cognizance of this front-page article, published during Naomi’s hospitalization.) Whatever strength Naomi had assembled during her 30+ years of careful nursing fell victim to Lenox Hill’s abuse and utter inattention to this underlying condition. Discharged in grim condition on March 17, in agony, she required hospitalization only two days later. We chose Mount Sinai Hospital, a far more humane institution. But it was too late: she died at 11 PM Thursday March 26. As death approached, I sang to her: “September Song,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and, as she had always sung to me in troubled times, “Hush, Little Baby, Don’t You Cry.”

--Jesse Lemisch, March 29th, 2015

Remembrance from Amy Kesselman and Virginia Blaisdell

Originally published at Wellesley Centers for Women Online

Naomi Weisstein was a multitalented, passionate, visionary feminist whose contributions to women’s liberation encompassed an insightful critique of psychology, creation of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band, and articles about science, music, comedy, and feminism. Naomi was a pivotal figure in the development of women’s liberation, both nationally and in Chicago. As an experimental psychologist, she exposed the misogynist assumptions of psychologists in her path-breaking 1968 article “Kinder, Küche, Kirche as Scientific Law: Psychology Constructs the Female,” which made a powerful argument for the effect of social expectations on women’s experience.

In bed for thirty years with a severe case of a disease that has had many names but few treatments—chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS); myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME); and most recently systemic exertion intolerance disease (SEID)—Naomi battled heroically to keep herself engaged and productive. Information on the disease and its new name can be found here. Naomi died of a rapidly growing peritoneal ovarian cancer.

Virginia remembers:

The Tachistoscope Affair is what brought Naomi to New Haven in 1962. She was a second-year graduate student at Harvard, and her PhD research necessitated the use of a tachistoscope—a machine that flashes images for very brief times. Milliseconds. Harvard of course had one, but they wouldn’t let her use it. She’d break it, they said. She admitted that was probably true, since the machines broke all the time. Yale, however, graciously (or perhaps competitively?) allowed her to use theirs, so she spent her research time in New Haven.

During her first year at Harvard she was appalled by the fifties-era datingrituals, which required the girls to wait demurely for the guys to ask them out. In what was probably one of her first feminist actions, Naomi organized a group of women graduate students to take notes on the quality of their dates. They then constructed a ranking order of date desirability (including the guys’ names) and passed it around among themselves and to any other woman who was interested. All of a sudden they had the power: the guys wanted to improve their standing, and the women got to pick and choose and make the guys grovel.

Amy remembers:

I met Naomi in 1967 in Chicago, where we had both been involved in the radical movements of the period. After a movie we had an exciting conversation about the idea of agency in its various forms—Naomi in science, me in politics—both of us arguing against the idea of people as passive victims of circumstances. I was electrified by her brilliance. For more about our friendship and our political work in the Chicago Women’s Liberation Movement go here. In the galvanizing discussions in the Westside group, an early women’s liberation group in Chicago, Naomi’s radicalism, her irreverence, and her belief in our ability to generate a new world pushed our thinking deeper and wider. [Quote from Naomi]

In 1969 members of various women’s liberation groups in Chicago decided to form a city-wide organization to coordinate activities and help shape an independent women’s movement. Not all radical women activists in Chicago agreed with this project, and we worried that our founding conference would be disrupted by people who believed we should work within the male-dominated left. Believing that we needed an activity that would bring women together, a group of us, including Naomi and me, set about researching material for a play about the history of women’s resistance. The play began with Naomi and me dressed as witches, playing two different approaches to building a movement. Naomi was Witch #1, exuberant, inventive, and a bit wacky, and I was witch #2, humorless and a bit pompous:

Witch #1: I have an idea.

Witch #2: (turning around, walking away) Oh no, she has an idea.

Witch #1: (taps her on shoulder) Get the pot.

Witch #2: (wheels around) Get the what?

Witch #1: The pan, the cauldron. I’m going to throw in everything I hate, and then the revolution will happen.

Witch #2: Wait a minute. Wait a minute. Two steps backward, one step forward.

Witch #1: All right. (walks 2 steps backward, 1 step forward)

Witch #2: That’s a metaphor.

We then threw various implements of women’s oppression into a pot outfitted with a smoke bomb. After it detonated, members of the audience read quotations from women rebels from around the world and several centuries. At the end of the play, in response to shouts of “Who are you?” the two witches recited a litany (which Naomi wrote) that began.

"I am all women, I am every woman. Wherever women are suffering, I am there. Wherever women are struggling, I am there. Wherever women are fighting for their liberation, I am there."

After verses that described various feminist struggles, the litany ended

"And where there are women too beaten down to fight, I will be there; and we will take strength together. Everywhere. For we will have a new world, a just world, a world without oppression and degradation!” (See the full litany here).

Looking back, we developed an impressive collection of quotations, before the burgeoning of the field of women’s history. The play worked. Everyone was crying and laughing at the end, and there was no disruption. Full script is here.

Virginia remembers:

Naomi brought her considerable musical and performance talents to her efforts to interrupt the sexist hippie rock and roll anthems of the various seventies liberation movements. “Every fourteen-year-old girl in America listens to rock,” she said. “They want to hear rock music that doesn’t degrade them.” So she formed a band in Chicago, with women who tended to be more feminist than musical, but totally turned on to play rock nonetheless.

I visited her in Chicago and saw one of their early rehearsals, and I was turned on too. I went back to New Haven and found some women in our local feminist group who wanted to form a band. Naomi and I collaborated on everything about our bands: even our names were nearly the same: the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band and the New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band. Names long enough to require a very big banner, we thought.

We also collaborated on figuring out our mission and how to convey it. Chicago outdid New Haven on performance, especially because Naomi was so good at presenting what the band was trying to do, in raps between the songs. I wouldn’t exactly call our music “polished,” but both bands succeeded in the area of Total Audience Involvement among the feminist and new left communities.

Amy remembers:

Naomi was an inspiring speaker who often brought audiences to their feet, as she mined her own experience with the entrenched misogyny of the scientific establishment. She described herself as “Naomi in wonderland, blunderland, plunderland,” as she told the story of scientists trying to steal her work.

Virginia Remembers:

Even though I met Naomi the Serious Scientist, I came to know her as a hilarious, impish, adventurous, and deeply playful person. She loved Lenny Bruce’s way of shredding the hypocrisies of convention. She even had dreams of becoming a stand-up comedian. It was her pursuit of destabilization—of scientific conventions, cultural orthodoxies, expectations of “femininity”— that made it so invigorating to be in her orbit.

Amy remembers:

A recent post on this blog by Laura Pappano exhorted readers to challenge the rape culture that nurtures sexual violence. Pappano describes the many ways women are faulted for “asking for it” by the way we dress and where we go. In 1974, Naomi evoked women’s experience in a wildly funny but powerful comedy routine about rape, which she performed in several cities. How can one do a comedy routine about rape? Naomi did it! It was hilarious because it tapped in to the common experience of living with ever-present menace

"I’m walking down the street and, as usual, my head’s a little bit to one side, because I won’t look guys directly in the face or they’ll think I want it, and I won’t look down at their pants or they’ll know I want it, so I’m looking at their necks."

The routine ends with a call to action to stop “a system that feeds itself on violence, on blood, on our blood.” (See the entire routine, “Saturday night Special: Rape and Other Jokes.”)

All of Naomi’s work—her comedy, her music, her organizing—was infused with a vision of a radically transformed, just and generous world, which would be brought into being by the collective action of many groups fighting together for their liberation. Her death leaves a cavernous hole in our lives.

Naomi’s papers are at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute. They provide a rich resource about her many interests and activities that we hope people will explore.

Amy Kesselman was involved with women’s liberation in Chicago. She is an emerita professor from SUNY New Paltz, Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program, where she taught women’s studies and women’s history for 31 years. She is currently working on a book about feminist activism in New Haven, Connecticut from 1969 to 1977.

Virginia Blaisdell is a photographer and a graphic designer for UNITE HERE International Union. She was active in the New Haven women's liberation movement during the sixties and seventies and was a founding member of the New Haven Women's Liberation Rock Band and an editor of "Sister," a local feminist magazine.